Journal Entries

September 1, 1940

A warm, sunny, perfect day. Tired out. Had been standing by until 4 this morning. Painted this afternoon until about 4.30. Slept till seven. About nine I went for a walk by the river. The intense colour of the day still lingered on the buildings, in the sky and on the water. But there was a unity about it as of the night that was about to envelop it. I stayed and watched the darkness slowly approach and I felt as though it all belonged to me and nothing else mattered in the world.

September 3, 1940

I cannot accept that belief in a sort of intimate personal relationship between God and the individual. I can see no evidence of it about me nor reason why such a relationship should exist. Beyond that I have a belief in someone who, for me, is God, but he has not got those curious likes and dislikes that the majority of Christians attribute to him. They make him in their own image. Do I make him in mine?

Letter to Marion

5 September, 1940

Chelsea, Thursday

Dearest Mog,

I had both your letters yesterday, although I see the first was written last Saturday. I am glad my present for Julian arrived safely.

These days my time at the depot is practically a 24 hour job. I never take my clothes off whilst I am there and even have to keep all equipment on most of the day and night. There was a big raid last night and I really thought we were going out at last, however, very few actually got through to central London, although Carlyle Square stretcher party were called out. A bomb fell somewhere at the top of Sloane Street but did not explode. My own work is suffering badly and will do so as long as things are like this. But it had to come and must just be gone through with, it won't last forever.

I will send you at least eight pounds each month and more when it is possible. If your cheque reaches me a bit late sometimes I can always send the thirty shillings that week and make it up the next, when it has arrived.

I did my first aid exam last night. The sirens went when there was still an hour to go so I didn't have time to run over carefully what I had written and so missed a few points. I expect they will allow for that. Anyway, I think I have passed it with a bit to spare.

The drawing of Simeon Solomon is a head, a late one, feeble in a sense, but most interesting. I have also acquired, in a roundabout fashion, a very fine oil of a nude man. It may be Italian but it has a suggestion of an early Géricault. It's a fine bit of painting though and that's all that matters to me. It wants relining but that will have to wait.

I am worried about you in a way and yet not greatly worried, if you understand what I mean, for I have no feeling that anything bad will happen to either of you.

I am happy the christening and birthday went off well and I hope with all my heart that we will have a real celebration next September when we will be together.

Thank you for writing such wonderful things to me.

On no account take any notice of Peter's stupid methods of training children. Your own ideas are the only reasonable ones and I would be most unhappy to think of Julian ever being treated in any other way.

Love to you both, I will be writing again on Saturday.

Clifford

PS

Your letter with the cheque came just as I was going to post this.

I will send £2 when I write on Saturday.

Don't worry about I am feeling very well and I love you,

Clifford

Thanks for Fairlie Harmar's letter. The show opens next week. I will let you know what it is like.

Journal Entries

September 6, 1940

A week of raids most of the day and night*. I am too tired to paint on my days off duty. I did, however, make a copy in pen and wash of a reproduction of a little nude by Watteau. As far as one can tell from a reproduction the picture is magnificent. It reminds me of Manet. There is the same elimination of half tones, big simple drawing and exquisite handling of the edges.

* Most of these events in this particular were probably air-raid warnings rather than actual raids in which bombs fell on London.

Watteau must have thought she was very lovely and he has made me think so too. It's grand to be able to do that.

Last night we saw three brilliant flares slowly descending apparently directly above Lots Road Power Station; in reality probably some distance behind it. They floated down very slowly, lighting up the buildings. Fascinating and beautiful to watch with their scarcely discernible little tails of smoke. No bombs followed them. Towards London the sky was red. Hortensia Road fire engine was called.

These nights are warm and starry and they have an air of unreality. Sometimes one hears the sound of a distant bomb exploding, there are flashes, and the long beams of the searchlights are everywhere. Now and again the noise of a plane that one can never see, and then a number of shells will burst, high up in the night sky. Somewhere, I suppose, amid those shell bursts is a German plane and down below, all over London, people like ourselves are suddenly blown to pieces or horribly maimed. And in Germany too the same thing is happening.

Hour after hour we sit in the dimly lit corridor with all our equipment on. The piano has been dragged out of the recreation room, someone thumps popular songs and the men howl the choruses. Others play 'Housey Housey' and above the singing Mac's voice can be heard yelling the numbers, 'Clickety click! Sixty-six! Number seven! Blind twenty! Kelly's eye! Top of the 'ouse! Ninety!'

I vaguely try to find some pictorial interest in the scene, but I am far too tired and the tall rubber boots make my feet and legs ache. I slowly go over in my head all the things I have done, the pictures I have painted, and the ones I am going to paint. I think of Marion and of my son and I wonder if I will ever be able to help him to understand that in spite of its apparent stupidity life is a wonderful experience.

About 3am., after the 'All clear', we are told to 'stand down'. Still dressed, I fall asleep in a deck chair, and about 6 a.m. I wake to find that someone has put a rolled-up blanket between my head and the back of the chair and has tucked another blanket round me. My corporal, Charlie Barrett, who has a large butterfly tattooed on the back of his right hand and who can never open his mouth without swearing, is grinning at me. 'It got bleeding cold mate,' he says, 'so I covered you up.'

September 7, 1940

Bill came about four. Had tea. A raid not long after. We went out in the street and saw a few planes. Pretty violent gunfire. A lot of fire engines called out. 'All clear' about six.

Bill left at 7.30 and I got a bus to Putney*. Another warning at 8.45 or thereabouts. Took Mother to the shelter and decided to get home. There was a vast orange glow in the sky, down river. Marvellous. Made a few lines from the top of the bus to aid my memory of the effect. Had something to eat at Jimmie's restaurant. Walked home and arrived just before 10. I made a pastel sketch of what I had seen. Went to the Cadogan Club for a drink. The glow in the sky fiercer than ever. It must be a terrific fire. A little after 11 decided to go back and get a decent night's sleep. The door to the King's Road was open and just as I was going out there was a rapid swishing sound followed by a big thud which shook the building and the ground under my feet. Thought it best to shut the door and go down for another drink, which I did. Just before midnight I felt that I would get that sleep after all, so here I am. There are still bangs round about and a continual sound of planes.

* Putney was where the artist's mother lived, in Star and Garter Mansions, Lower Richmond Road.

Letter to Marion

7 September, 1940

Chelsea

Saturday

Dearest Mog,

Here is the money. It is just one raid after another now, sometimes seven a day. Nothing serious has happened at Chelsea but other places not far away have been getting a bad time. I will write more next week. Very tired now. Love to you both,

Clifford

Please write soon to me and tell me how you are.

Regrettably, most of Marion's wartime letters to Clifford have not survived. Here is a transcript of one that has.

8 September, 1940

Sunday

My Beloved Gog,

I was so very glad to get your letter. After the news of last night's raid and all those casualties. I simply exist for your next one. I'm anxious to the point of franticness about you. It's no use telling me not to be. I just sit here visualizing horrors with you out having to be in the midst of them. If only the brutes would stop. What can be the outcome of all this senseless destruction? I know you've a wonderful faith of our survival but I'm truly frightened. So needless it all is - so utterly unintelligent.

Last night strangely enough was a very quiet one for us. We were so tired, and having had sleepless and broken nights all last week, decided to go to bed at 10 sharp. I fell into a very deep sleep and it seemed hours afterwards (in reality only 1½hours) that there was a hammering on the door and Peter was urgently told to hurry up and dress and be out at the Home Guard post at once. The whole village had manned the posts and dug-outs. Harmer - the bus man - came along soon afterwards and talked to us through Pearl's bedroom window. We asked him what it was all about but he wouldn't tell and begged us not to go out but to stay where we were.

Shortly after he left, Peter returned for a candle - his post is at the Cricket Pavilion in the next field - and said there was talk of troop-carrying barges seen to have left Brest, working their way towards Ireland! And he didn't return after that until 9 this morning. He's been called out again tonight, poor thing, so perhaps there's something in it. It seems some people now say the Germans were heading for the South Coast and some adhere to the original story. I don't know if there's any truth in either statement but there seems to be a scare somewhere. The wireless - peculiarly - said nothing about it today.

Hack on his way from Blandford camp to Plymouth stopped off here for tea yesterday with two colleagues. It was wonderful seeing him and I was most regretful when he had to leave. He looks very well indeed. And most smug about something. I do sincerely hope what he's doing is effective when it does - if it does - come to invasion.

I'm so dreadfully sorry you haven't been able to work my darling. I wonder if, after all, you shouldn't have retired to the country and waited to be called up, working meanwhile. It's so difficult to know what to do in a dreadful time like this.

A bright spot for me this week - last week I mean - was a present for Julian from Stanley. An egg cup and spoon in Jensen's silver. It's perfectly lovely. A simple economical design but beautifully heavy and rich looking. I'm so pleased with it! Do please thank him. I have already.

Oh, my dearest Gog, my love for you is so complete and yet it can't rise to a consistent faith like yours. I'm so very worried. Do, do, write soon.

Your own Mog

who covers you with kisses.

Julian is well and progressing nicely. Shouts Moo! Boo! At the cows across the wall. And sometimes when they're not here.

Journal Entry

September 9, 1940

Yesterday we had nearly ten hours of bombing. On gate guard in the early hours of this morning I heard the bombs rushing over my head and exploding some way beyond. Direct hit on a shelter in Beaufort Street. Nearly all the people in it killed - mostly women and children I believe. Bomb fell in King's Road opposite Paulton's Square. Big fire from gas main. Another bomb in Cheyne Walk near Whistler's house; also one in south Parade near my studio. A hell of a night.

Beadle, Jeff and Bill came in at tea time. Bill stayed, the others left about five. The sirens had gone. Suddenly the now familiar sound of a plane, then the noise of a falling bomb. Too damned close. A terrific explosion. A blast of air and grit through the open window. My pictures jumped forward from the walls and slapped back again. The whole building rocked. 'Let's get out,' we said, almost together. As we made for the door another bomb fell. It seemed closer still. We hurried down the stairs and across to the Polytechnic basement.

Two huge clouds of smoke hung above the King's Road, about sixty yards away. Fainting women in the Polytechnic basement. 'All clear' quite soon. Went out to look at the damage. Three houses in Bramerton Street entirely demolished. Greatly fear Doctor Castillo's is one of them, and I wonder if he was there, and his wife and children.

Walked along past the Chelsea Palace* as Bill wanted to phone. Dozens of shop windows smashed and the roads and pavements thick with broken glass. People looking around for bits of shrapnel, and finding it.

* The Chelsea Palace, now demolished, was a music hall in the King's Road. The artist loved music hall and melodrama (he went to see Tod Slaughter in Jack the Ripper four times) and bitterly regretted their disappearance.

Going back met Willson Disher*. We all went to the Six Bells for a drink. The bowling green covered with earth and broken paving stones and bricks. Bill took four small paintings back to Hampstead. Ones I would like to save, and I am not so sure about Trafalgar Studios** after this.

* M. Willson Disher, drama critic and showbusiness historian, whose books include The Greatest Show On Earth (G. Bell, London 1937), a history of Astley's Amphitheatre, where Charles Dickens had been an enthusiastic spectator.

** Trafalgar Studios survived the Blitz but was later demolished. It stood on the right- hand side of Manresa Road, about thirty yards from the King's Road. Clifford Hall first moved there in 1933, to studio Number 4. He subsequently moved to Number 8 in 1937, and the kitchen there was on the opposite side of the corridor with a front door of its own.

Went to Putney for the night. Sirens soon after I arrived. On my way a part of the King's Road roped off and guarded by soldiers with rifles. Firemen hosing the smouldering remains of the Bramerton Street houses.

On my way to the bus met Dinah*. We went to look at the remains of the Cadogan Club. It has almost disappeared. Kitchen blown out and nearly every bottle of drink in the place smashed.

* Dinah was an outstandingly beautiful artist's model. Clifford later used to meet her and her husband, Jack, on his visits to Chelsea in the sixties and seventies.

Writing this in the shelter at Star and Garter Mansions. Mother is asleep. Five other people from the flats also here. Very cheerful, and seems pretty quiet outside.

Blitz

CLIFFORD HALL'S JOURNAL ~ 1939 - 1942 Page 7

including letters written to his wife Marion and some other correspondence

Letter to Marion

9 September, 1940

Trafalgar Studios, Monday

My dearest Mog,

This is just to tell you that I am quite safe and very well and that I hope to hear soon that you and Julian are too.

London got hit badly last night and on Saturday. On Saturday all the sky towards city was brilliantly lit up by the big fires burning at the Docks. And against this orange glow the searchlights paled to a delicate opal green colour. I had to go home and make a pastel of it and I hope to paint from it sometime this week. Last night was really bad. We were bombed from 8.30 until 5.30 this morning with hardly a break. At one time I was on gate guard, I could hear the bombs rushing down and across the sky. There were terrific explosions. Beaufort Street got it badly. A fire started in the King's Road just opposite Paultons Square, the petrol in a garage caught and a gas main. The road was alight from side to side. Chelsea Square had it too.

I walked back this morning past the fire which was still burning a little, wondering if the studios would still be there. They were. All the pictures I love, perhaps too much, and not even a pane of glass cracked. It is really a good thing that you got away when you did, for I fear it is going to get a lot worse yet. But remember what I told you and do not make yourself mad with worry, but come back to me, someday, beautiful as you always were - because I will be here, I promise you.

All my love to you both,

Clifford

Journal Entries

September 10, 1940

As I feared. Castillo's wife and children were killed. He was on duty at the First Aid Post.

There were seventy people in the Beaufort street shelter hit on Sunday night. Only seven were got out alive.

Fairlie Harmar and her husband were rescued from their house in Cheyne Walk. A bomb burst the water main in the street in front of the house. The rooms were flooded. Furniture and pictures floating about. Perhaps my little panel of Church Street amongst them.

September 11, 1940

Last night the closest - so far. In the basement canteen the doors were blown in and we were covered with broken glass from the windows. A man coming from the lavatory was thrown across the yard and hurt. Other minor casualties. There was something very like panic for a few seconds. Saved by Corporal Rowe who went on calmly pouring out tea and telling everyone not to be a lot of bloody fools.

The bombs continued to fall. All very near us. Frightened men, women and children came into the depot looking for shelter.

Soon a number of shops in the King's Road were alight. The wall of St Mark's college blown down. Our cars damaged. An oil bomb started another fire in the yard. Two of our squads went out. Not many people hurt and only a few killed. Most of them were in the shelters, which were not hit.

Had to wander round the grounds at 5.30 this morning looking for a time bomb. We failed to locate it. Two were discovered later in Edith Grove and Gunter Road.

Shattered windows and debris everywhere. Groups of people, homeless, standing about aimlessly. One or two of the men complain that the depot is a death trap. Right near Lots Road Power station and not even sandbagged. Talk of not coming back, but I don't take that seriously. A few even say it is not worth going on. It's knowing their wives and children are in danger and may be killed.

More raids today. Churchill's speech most unimpressive*. I don't like the look of things at all.

* Given the iconic status of Winston Churchill's wartime speeches, this comment may, in hindsight, seem unduly negative. However, the Speech to the Nation that Churchill delivered on September, 11th, 1940, is far from being among his most inspiring, and therefore, it is one of his least well-known.

"Every Man to his post", Sir Winston Churchill's real speech on the 11th of Sept. 1940.

Letter to Marion

11 September, 1940

Wednesday

My dearest,

I was very glad to get your letter this morning and to hear that you were both well. London has been getting it really badly for the last week or so, far worse than the papers say, naturally. And Chelsea has had a pretty bad time. Last night was rather grim and I was scared for a few seconds but here I am quite safe. I am spending my off nights at Putney for the time being. I can look after mother and also it has been too hot here to sleep in the studio. I do not want to tell you of all the things that have happened these last few days. It would only disturb you and possibly make you think that things are worse than they really are. I have only been in real danger once or twice and I still feel I will come through the whole thing. I can only say that you must try to have faith too and believe what I say.

I will write again at the end of the week.

Love to you both,

Clifford

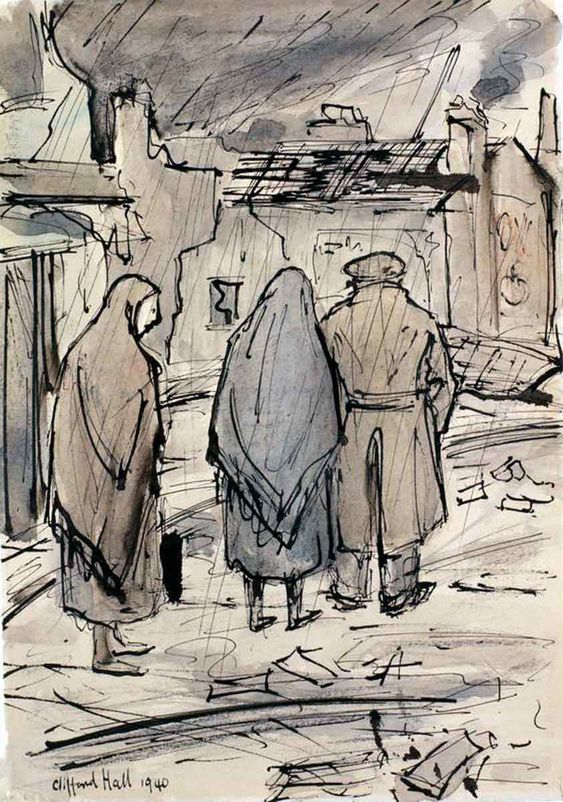

'Homeless', 1940. Watercolour by Clifford Hall. Collection: Imperial War Museum, London.

'Hortensis Road', September 1940. Sketch by Clifford Hall depicting an ARP man (probably a Fireman) getting some rest while on standby during the Blitz

London Can Take It

propaganda film

Produced by the British Government in October 1940, 'London Can Take It' is narrated by American journalist Quentin Reynolds and pays tribute to London and its people during the Blitz on the capital.

The film's huge impact at the time, especially in the USA, makes it historically one of the most important of the Ministry of Information's wartime films.