The drawing was then squared up and a full-size cartoon made, in clear outline. A tracing was taken of this, a thin film of Indian Red being then rubbed over the lines as they showed on the reverse side. The tracing was laid face up on the prepared canvas and the lines gone over carefully with the blunt end of a thin brush handle.

Sickert carried an agate mounted on a wooden handle and he used this for working through.

Now the picture was underpainted in three tones of Indian Red and Flake White, on a white canvas. The surface grease had been removed from this by sponging gently with warm water and Castile soap and sponged again with warm water (to remove any soap) before being carefully dried. The underpainting was very high in key. No medium was used.

Sometimes the underpainting was in Cobalt Blue and White or the cool parts might be painted in Indian Red and White, whilst the warm parts were underpainted with Cobalt Blue and White. This underpainting must be put away to dry, for 12 months if possible, before it was ready for colouring. We must 'continually prepare and lay down underpaintings 'as some people laid down wine', taking them out to work on as they became mature.

The date of preparation was to be written on the back of each.

Sickert painted a colour sketch from the model as a demonstration. Before touching the panel he mixed up all the main values on his palette.

He worked vigorously and quickly, rubbing the paint well into the surface and finishing with slightly more gentle touches made with a fuller brush. He borrowed my brushes and when he had done with them, after an hour or so, they looked like miniature chimney sweep's brushes, the bristles standing out at right angles to the ferules. He said he was sorry but he always treated brushes roughly.

And talking of right angles, his definition of drawing was 'the relation of all the angles that occur within the 180 degrees of 2 right angles'. And according to him, if one did this correctly the problems of perspective were automatically solved.

Some time later he chose a drawing I had made which agreed with his demonstration colour sketch and told me to square it up, enlarging it about 2½ times, and underpaint it. This I did and at another demonstration he coloured my underpainting using his colour sketch and my drawing. He also painted a monochrome from a Daily Mail photo of a wedding which he had previously squared up. The brush strokes were crisp and went across the form. He often said that all he told us could be found in William Hunt's Talks On Art long out of print, and this is largely true.

He came into the Evening Drawing Class only once and looked at the drawings. This was on his first day at the schools.

Ernest Jackson, the Professor of Drawing, asked him what he thought of the work. Sickert was not enthusiastic. At last he told Jackson he liked best my drawing and one by Morland Lewis. These were not, he hastened to add, particularly good drawings but we two had at least drawn the whole figure, whilst the other students only appeared to be interested in highly finished portions - shoulders and arms without hands, legs minus the feet and bodies lacking heads. Jackson never looked at Lewis and myself again. We had not been particular favourites of his and we did not mind.

The drawing class contained, in those days, a number of little figure studies by Thomas Stothard, some in pencil, some in ink, many highly finished. Sickert admired these greatly and sometimes went in, when Jackson had no class, to take another look at them.

Jackson always professed a very low opinion of Stothard.

Sickert had no time for students who did not work and his remark to a girl student who brought her pet dog to the Schools was withering.

He told a student* who showed him drawings in bright blue chalk that he was 'playing with loaded dice'. Black on white was what was wanted and he would make large crosses on empty spaces where he knew something had been omitted, demanding: 'What happens here?'

* The student was P. F. Millard. CH.

He divided pictures into two sorts. The ones in which something was going on and the pictures of 'yearning' in which nothing happened.

'Let us have people doing something. Working, making love, misconducting themselves but doing something.' And figures or groups of figures must not be shown as in a vacuum, always they must exist in relation to their surroundings. One could build up a picture by starting with a table or a chair or a bed.

He had little use for studies as such.* From the start we were encouraged to paint pictures and to make drawings to be used for that purpose.

* Brown's (Leicester Gallery) story of Sickert in his studio painting from his drawings laid out on the floor and walking over them, wearing hobnailed boots. Brown's horror - Sickert's drawings! CH.

I still have some of the drawings I did under Sickert, at least one of my colour sketches and a painting I worked out from these studies.

Sickert's insistence on good craftsmanship is a thing one seldom comes across now. The methods, or rather lack of method, encouraged in our art schools and made necessary by the Board of Education's examinations would horrify him as they do all painters trained in a sound tradition.

I have never known a master who gave so much, who was so inspiring to his students. As time goes on I realize that most of his teaching was so basically right it could be applied to almost any point of view - even the Abstract Boys could find something in it, and for all I know perhaps some of them have.

Of course all he taught was absolutely traditional and he would have been the first to admit it.

* * * * *

I have not yet said anything about my other grandmother*, whose husband died before I was born, and this is because I do not associate her so much with my early childhood but with later, when I was a student and my teens. She was born in County Wexford, at Enniscorthy and had a charming accent and very definite opinions. She was a tough old lady and lived almost to her hundredth year eating well to the end and never a day without her whiskey. As a girl she had been to Dickens' Penny Readings** and when my brother and I were little she sometimes read parts of his books to us. She read with great expression and possibly allowing for the natural talent for mimicry most women possess, she was able to give us a flavour of the great author's delivery.

*Annie Beatty, née Bishop, her husband's name was Martin Beatty; he died before Clifford was born and thereafter the family took to calling her Granny Bishop, possibly because of her strong religious convictions. GRH

**Charles Dickens used to give public readings of his works priced at a penny so that as many people as possible could attend. GRH

She had a maid, brought up by Dr Barnardo's Homes, almost a dwarf with a face like a monkey and a heart of gold. 'Poor little Emily'. My grandmother was most exacting. I painted a small full length of Emily when I was a student and I still have it.

It has long been on my mind that I never loved my father and mother as they deserved. As I grew up, I found I had little in common with my father. He loved old china, furniture, glass and other antiques and had fine taste except in painting, but modern work meant nothing to him. He was good and generous, but I could never in my heart quite forgive him for the occasional thrashings he gave me when I was a child, because, I think, I early guessed he lost his temper when he gave them; but I admired him immensely, for he was a courageous man. Neither of my parents could understand the work I was doing, or trying to do. They were proud of me but only when it could be shown I had accomplished something, like getting into the Academy Schools or winning a Landseer Scholarship, but without their help I should never have been able to survive as an artist. My father would have been truly proud had I succeeded in some form of athletics and that I could never have done.

I had forgotten until now the arrival of refugees from Belgium in 1914. A great number, men, women and children came to Twickenham, just the other side of Richmond Bridge, and some were given work in a munitions factory (the Peladon Works, by the river). A great many of the men were young and looked able bodied and the locals thought these young men should have stayed in their country to fight the Germans. The arrival of the Belgians had one effect on me for it gave me a glimpse of another kind of life. Some shops in the Petersham Road, near the bridge, were turned into cafés. There was sawdust on the floor, bright signs with foreign words, the fronts were open, and the customers sang and sometimes danced whilst a man played a piano. I do not know if they sold alcohol without a licence but they made quite a scandal and were soon closed. I was sorry for I used to like to stand outside and look in, surprised to see people so gay and happy.

EARLY LIFE MEMOIR -4

'The Rehearsal'1926, by Clifford Hall. An old b&w photo of a painting the artist completed while attending the RA Schools. It was later exhibited at the Belfast Art Gallery, Northern Ireland, in 1938 by the New English Art Club.

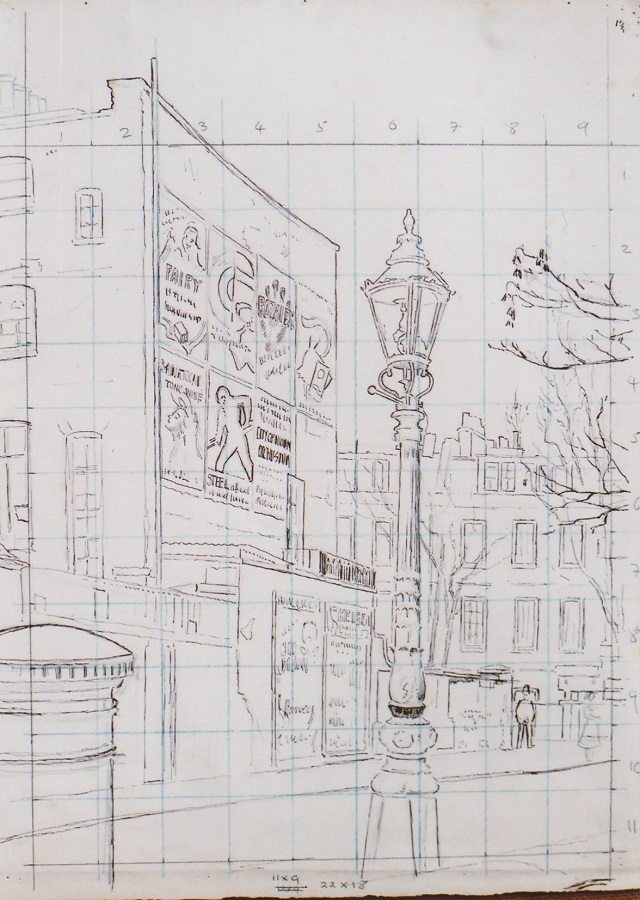

'Chelsea Street Scene',1949 by Clifford Hall. This working drawing for a painting clearly shows the artist using the squaring-up method as taught to him by W R Sickert at the RA Schools.

Clifford Hall's maternal grandmother Annie Beatty ('Granny Bishop'). The young child with her is believed to be one of her four sons - i.e. one of Clifford's uncles.

Martin Beatty (1834 -1899) Clifford Hall's maternal grandfather who died before he was born. He was apparently born with the surname Betty but changed it to Beatty.