Someone suggested the Dingo, round the corner. An American battleship had put in at Cherbourg and a party of the sailors were spending their leave in Paris. The Dingo was full of them. Sam, a great hard-drinking fellow, was calling a round of drinks as we went in. He caught sight of John and, handing him a glass, said, 'My name's Sam. I don't know yours, but have a drink.' 'Mine's Gus. Good luck.' answered John. At the bar Eve Kirk explained to me that she was on her way to Rome. She looked very attractive in a green velvet costume and had great coils of carelessly piled up tawny hair, slipping out from beneath her hat. She was a very clever painter. There were a number of other women who seemed attached to John in some way. A kind of retinue. 'If only he would eat,' Eve said. 'It's very difficult. All the way from Marseille last night, it's long past dinner time now and still he's eaten nothing.'

About 1.00am, now back at the Dôme at the zinc bar, John decided to eat and started on cold sausages from a basket full on the counter. I vaguely remember him throwing the sausages about the bar. No one took much notice - they were used to worse than that in the Dôme - and I last saw him hurrying out, a trifle unsteadily, to a waiting taxi, with a woman - not one of the retinue. He did not reappear for two or three days and the retinue plagued Edwin for information. 'How should I know,' he said. 'I'm not his keeper.' Eve was very worried and I often wondered if she ever got to Rome.

It was a perfect summer and most days Rowley painted in the streets around Montparnasse, sometimes by the Seine and also in the quarter by the Panthéon, off the Boulevard St Michel. Faithfully about six, with his coat, trousers and hands messed up by paint, he would drop into his usual chair at the Dôme and call for a drink.

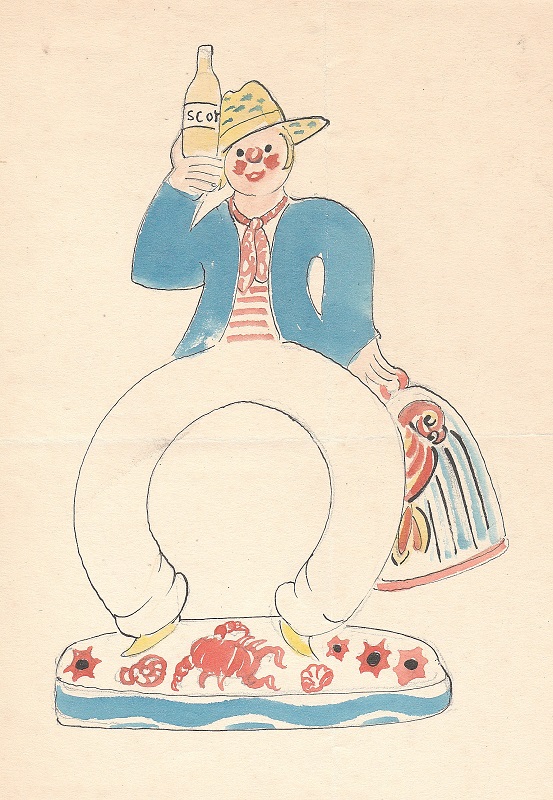

His was a personality that attracted, and moreover he was generous with his money. His corner of the terrasse was always crowded and noisy. He loved to sing 'Bollocky Bill ', 'Anthony Clare'. 'The Sentimental Skipper' and 'Toby'. He egged the others on to join in, but his voice could always be heard above the rest. 'The Sentimental Skipper' and 'Bollocky Bill' were two of his great favourites and Bill's adventures were the theme of one or two large and magnificently decorative watercolours that he painted during this period.

We were at the Dôme most evenings; or perhaps we would wander across the way to the Rotonde but the music from the dance hall upstairs filled the place, and it was never a great resort of ours. If we were hard up we might start on the round of the bistros, dirty little dens in which one drank standing uncomfortably at the bar, served by an unshaven, collarless patron, in the company of doubtful looking customers who were probably not so villainous as they appeared.

Drinks were very cheap at the bistros. I was often with Rowley. He did not like to be alone. Even when he painted he preferred to have someone with him, although he concentrated on his work. It was not difficult to realize that he had a perfect horror of being by himself even in those days. Later this desire for company at all times and at any cost became abnormal. So he stayed on in Montparnasse, held there, I believe, by its life and by the constantly changing drinking companions that it offered. Stayed there although another part of him wanted to be in the country during that perfect weather, painting the landscapes he loved.

He told me that he could not stand the country because there was nothing to do in the evenings. I suggested that he might try going to bed early and easing up on the drinking.

'It's no good Cliff, I could not sleep, and I always was a dirty bastard. Why I remember one time when I was a kid in Manchester some uncle or aunt came to see us and brought me a tiny toy boat. I was eager to float it and although now I remember there was a bath I could have used, the only place that occurred to me was the chamber pot in my room. I always did do things the most difficult way. At the Manchester Art School I missed the chance of a scholarship because I would experiment and not do what I was told. When I joined the army what did I choose to be? A bloody mule driver.' He was badly gassed during the Great War. In after years he blamed this as the first cause of his lung trouble. 'London was hell after the Armistice. I was ill and had no money. I was on the bum and could not work. John Flanagan* was knocking around too. A crowd of us used to take a studio and sleep on old newspapers with which we covered the floor. Flanagan was a good talker and a business man. He took the studio, and when the first lot of rent became due we just faded. We kept this up for a while, going from place to place, but landlords got wise to the racket and began to demand rent in advance. I spent some time in Stewart Gray's house. He was a crazy sort of bastard. He had a big house in Regent's Park. All sorts of people used to live there and hardly any of them paid rent. Stewart did not mind. He had had quite a bit of money left him. But things at last got bad with him too. We chopped up the furniture, even the banisters from the staircase, to make fires. The gas and light were cut off and we actually sold the bathroom taps for old iron. I used to spend days in the Café Royal on one beer, and I was forced to sleep on a table in one of Mrs Merrick's night clubs. The table was not free until about 4 or 5 am. when the club closed, and it was a hell of a business waiting around. She was a good sort.

* This was probably the British painter John Flanagan who had a relationship with Gracie Fields. GRH

'One day I met Augustus. He asked how things were and I told him. He sent me down to his place at Fordingbridge, gave me paints and canvas and let me use his studio. I was able to have a show some time after and it was successful.

'I had an amusing time with John. He was very good to me but we sometimes quarrelled like hell. I remember once at dinner he threw the joint at me. I picked up the cat and threw it at him. Only one thing I would not do and that was to let him drive me in his car. He was a crazy driver. He said driving was easy, like drawing. You simply fixed your eye on a certain point and aimed straight at it. The villagers got out of the way pretty damn quick when they saw Augustus coming. Once he landed up in the middle of a pond and another time he drove smash through the drive gates to the house.'

Rowley's marriage was not a success. How could it have been? Anita, too, drank hard. She bit right through her lip in a violent attack of D.T.s. I should say that Rowley never needed much encouragement where drinking was concerned and he was always the first to admit that, but life with Anita did not help. They had made a bad start. They had a room in the Tottenham Court Road. The first meal she cooked for him was a steak. 'I did not like the look of it so I pitched it out of the window. It landed on top of a passing bus, dish and all.'

He always acted on impulse. He was impulsive in his work too, and it gave his paintings a vitality that so many of his contemporaries lacked. And when he had been drinking, this natural impulsiveness, perhaps recklessness, had a dangerous side. He was walking one evening some yards behind Aicha, a little fellow with a mop of fair hair hanging on his shoulders. Aicha drew shockingly bad portraits of customers in the large cafés. He always had a portfolio under his arm. 'Don't like his hair!' exclaimed Rowley, and suddenly running forward shouting 'Take that you bastard!' he struck a match and Aicha's hair was alight. 'He had a hell of a job beating it out,' said Rowley, chuckling over the incident. It shocked me, although I knew he could not have been sober when he did it.

It is after midnight. I want you to see the Boulevard Montparnasse running wide and straight, with its trees on either side, its cafés ablaze with light, their orange, red, white, yellow and blue awnings, and with all the brightly coloured chairs and tables occupied. The pavements too, filled with a vast crowd passing up and down the Boulevard. Sightseers, artists of sorts, respectable bourgeois fathers taking their wives and ugly children for a late stroll in the warm summer night. Smartly dressed girls pass and repass, their high heels making sharp staccato beats on the pavement. Negroes, men of every nationality are among the crowd. There is an officer of Spahis in long white Moorish burnous and red fez, a brilliant note flashing against the duller civilians. As I recollect the scene, men seemed to predominate. The girls, beautifully made up, sat outside the cafés and the men passed by staring, always staring.

If you meet a friend on the Boulevard you must try to find a vacant table inside or outside one of the many cafés. It is utterly impossible to stand and talk, for the slow-moving throng on the pavement inexorably bears you along with it. You are swept apart, not violently but quite surely, and escape presents itself only in a side street or in a café.

And the Dôme corner was the true centre, the very heart of it all. The interior of the cafés and restaurants were packed too. Stiflingly hot, thick with tobacco smoke, the air heavy with the presence of the perfumed women, with delicious whiffs of cooking and filled with a steady yet rising and falling clatter of conversation shot through with the voices of the waiters as they shouted their orders. From outside came the accompaniment of the endless traffic flow, the hooting of taxis and the clanging tram bells. There were still trams in those days.

Here and there in the interior a game of cards went on, but most people just talked, smoked and drank. Some nights a fight would break out, almost always inside, no one ever knew how. Usually the original contestants were drunk, but others would join in, and sometimes a real roughhouse developed. The waiters then advanced with full soda-water siphons, aiming so as to direct a steady stream in the fighters' eyes. As soon as a siphon was emptied, another waiter standing behind the first passed forward a full one.

Rowley was inclined to get mixed up in these affairs and although not particularly strong physically he still had, in 1928, a nervous wiry strength and was able to lash out with amazing speed, putting every ounce of his energy into the blow.

The ROWLEY SMART MEMOIR -3

Clifford Hall. A drawing by Rowley Smart made in the Dingo Bar, Montparnasse, in 1928.

Portrait of Edwin John, 1927, by his father, Augustus John.

Copyright: Estate of Augustus John.

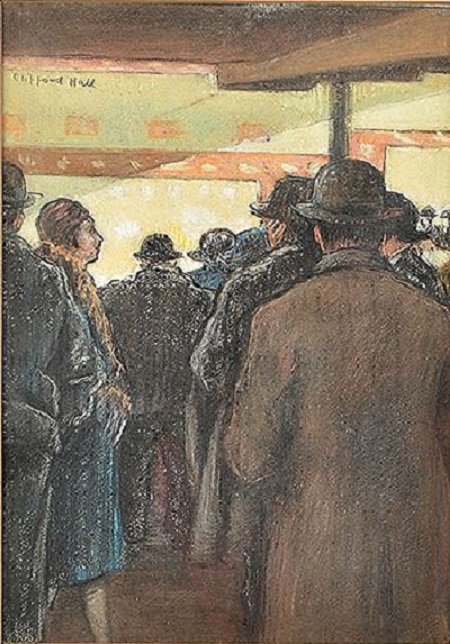

Queue outside the Moulin Rouge, Paris, by Clifford Hall

Cartoon of Bollocky Bill the Sailor by Rowley Smart

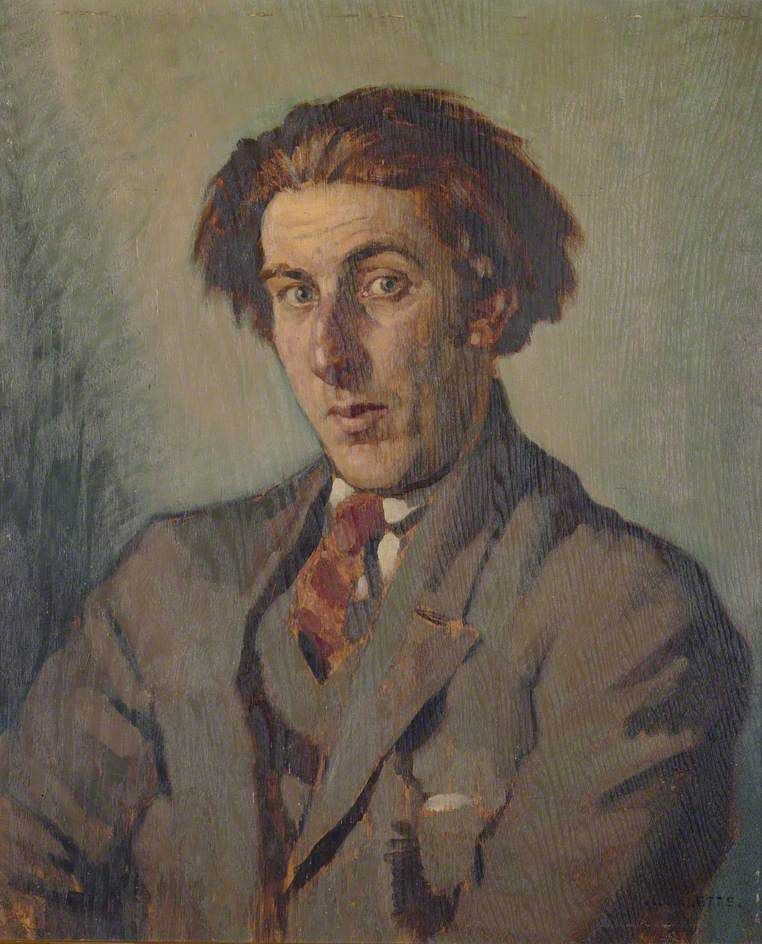

Portrait of Rowley Smart by Adolphe Valette (1876 -1942). Now in the Manchester Art Gallery Collection.