Serious fights, however, occurred very seldom. Heavy, consistent drinking was not the rule. I cannot remember more than a dozen habitual drunks in the whole quarter and I remember them because they were altogether more thorough, more hopelessly consistent than the type one sees in London. Montparnasse must have been a drunk's idea of Heaven. No closing hours, and almost all the tough drinks were cheap. If he was a foreigner, and all of the drunks except one were foreigners, he had the advantage of the exchange. A tolerant police force had never been known to arrest a man for mere alcoholic incapability. I have often seen a couple of agents carry away a drunk, place him carefully on a seat, pick up his fallen hat and rest it by his side, take what money he had left in his pocket and put in its place a piece of paper stating the amount with directions to call at the police station and claim it the following day. Practically all the hard, never-let-up drinkers were American, English or Scandinavian. Only one, Georges Mergault, the poet, was a Frenchman.

Georges spent his life in the Quarter*. He had no home but sat in the cafés most nights. Once, in the summer, he tried sleeping on one of the stone benches in the Luxembourg Gardens. There are a number of these and behind each stands a statue of one of the Queens of France. We asked Georges what sort of night he had had. 'Terrible. I chose Marie de Medici. She's as hard as a rock.'

* See "Fame", a short story by Clifford Hall inspired by the poet Georges Mergault. GRH

Gradually the lovely violet grey evening changes to night. But from one's seat on the Dôme terrasse it was impossible to see the stars. They were dimmed by the blaze of light from the street lamps, the open cafés and the coloured strip lighting which flickered along the facades of the buildings. One was held, as it were, in this pool of illumination that yet stopped abruptly but a few yards away from the Boulevard. Turn away, if you could, and walk down the rue Vavin towards the gardens of the Luxembourg and immediately you were in comparative darkness and the sounds of the Boulevard gradually became fainter and at last died. It was as if one had left a brilliantly lit crowded room and allowed the door to close with infinite slowness.

In the doorway of the Dôme Granowsky, the painter, leant with an easy grace, a red carnation held between his strong white teeth. He surveyed the crowded scene with the air of a proprietor. He, at least, could remember when the Dôme was just a little bistro. Foujita appeared. The Japanese painter wore his deep black hair cut in a fringe. He was dressed in an American tuxedo with a beautiful white silk shirt which held diamond studs. Diamonds sent flashes from his ears as he turned his head to fondle the Siamese cat that perched on his shoulder, and he wore a straw hat with a coloured band. Two gorgeous women accompanied him. He did charming work and was very successful.

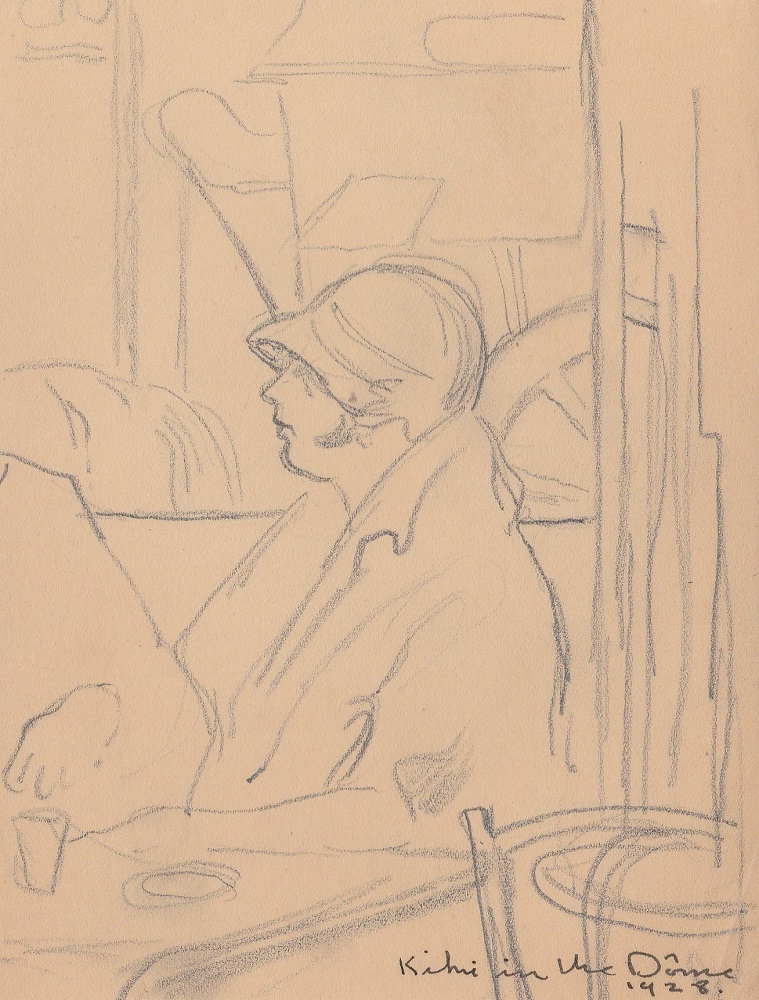

The exquisite Kiki, artist's model and the queen of the Quarter would be there, her make-up and toilette a symphony in lemon yellow and mauve with the Indian red of her lips striking a bizarre note.

And past it all marched a strange uncouth man. His capped, stubble covered face looked pale and ill. He appeared unaware of his surroundings. Summer or winter he wore a threadbare, patched overcoat. He carried a long staff, shoulder high, and handled it as if it were a punt pole. He was always referred to as 'The Gondolier'. He never spoke, never stopped, but almost throughout the night made his slow perambulation through the noisy crowds. Round and round the triangular block of which the Dôme served as a kind of blunted apex. Along the Boulevard, round the corner, and so by way of the rue Delambre and the dark rue du Montparnasse to the Boulevard again. He appeared, vanished and reappeared among the seemingly happy crowd. The skeleton at the banquet of gaiety. A silent reminder of another, more sinister aspect of existence.

Rowley never missed a night. Nothing could drag him away. Only once during all those months. Jo, a little French girl with whom he lived for a few weeks began to get really concerned about the sort of life he was living. He promptly left her. 'She kept on at me and actually succeeded in making me waste an evening at the cinema.' Jo consoled herself with a succession of American sailors, and finally died of T.B.

He boasted, as most men do, of his affairs with women, yet I remember him telling me one night, in one of those strange lucid intervals that sometimes came to him after a day and a night of steady drinking, that he was 'played out for that sort of thing years ago'. But in the breast pocket of his coat he carried a tube of ointment against infection. 'An American sailor gave it to me and it's absolutely certain - if you remember to use it at the right time.'

He loved to tell the story of the patron of the hotel who came to him one morning and said that he had no objection to Monsieur Smart bringing home a different woman every night. No objection at all; but he felt that when Monsieur Smart brought back the same fat negress three nights running in succession his hotel might begin to get a bad name!

Then there was the story of Rowley being taken to the American YMCA by Sam and a lot of other sailors; they were all rather merry and Rowley tripped over the mat as he went in and he swore violently. At that moment a clergyman was coming down stairs - 'Who is that terrible person you have brought here? The man is drunk.'

'Oh no, he's not drunk sir' replied Sam, 'he's a genius.'

About the end of November1928 I left Paris and I did not see Rowley again until the following year. We wrote to each other regularly, however.

I believe that sometime either during 1928, whilst I was still in Paris, or during the early part of 1929, he returned to England for a few weeks. But I cannot be sure.

I think it was in the June or July of 1929 that I returned to Montparnasse. Rowley was then in Moret. One day, about lunch time, a loud voice called my name as I went along the rue Delambre to the little restaurant opposite my hotel. It was Rowley. He looked well, the country had done him good. He had just come up for a couple of days to see how the booze-fighters were getting on. He had 300 francs and a toothbrush for luggage. The toothbrush pushed its head out of the breast pocket of his coat, alongside the famous tube of ointment that was 'certain if you remembered to use it at the right time'.

Well, we went off to lunch at Djguite, Boulevard Edgar Quinet. Then to the Dôme, then to the Rotonde, and on to the Dingo. Montparnasse had us again. About 2 a.m. Rowley's 300 francs were spent and I had got rid of an alarming amount of my small store of money. Also he had nowhere to sleep. I had a tiny room in the Hotel Delambre so we went there and tossed a coin for who should have the narrow single bed or its mattress which we had laid on the floor. I remember Rowley won the toss and chose the mattress. I think he got the best of it. The springs in the bed were positively diabolical.

I painted the following day and arranged to pick him up at the Dôme that evening. He had decided to stay on for a few days and had managed to get hold of some more money. He told me that he had originally gone to Moret with a Finnish girl. I remembered seeing her one night in the Dingo during the previous year. She was very quiet, with reddish hair, grey eyes and a good complexion. Rowley told me that she had helped him a lot. He had really fallen for her and she used to go out with him when he painted. 'She used to help me fix my compositions. She would say, "Now you just take in so much and finish the picture there. Don't take in that bit on the left," and so on.' At that period Rowley's chief interest was in colour and light and I had noticed that his compositions were often too little considered. It appeared she had quite reformed him too. They went to bed at 10 or 11 o'clock. But she had sworn that if ever he got really drunk again she would listen to no excuses and leave him for good. She had enough to live on and could do what she liked. There is no doubt that she was really fond of him. Maybe she loved him.

It did not last. Some of the old crowd from the Dingo came to spend a weekend in Moret. A post card was sent to Homer Bevans telling him that you could get a bigger shot of Pernod for less money in Môret than you could in Paris. Homer arrived by the next train. That night Homer and Rowley were hopelessly drunk. The Finn left next morning.

And now Rowley was back in Paris again and it was impossible to do anything with him. Money for some pictures came from England and in a way it made matters worse. But he did not forget her easily. He often spoke of her at that time. 'She was a swell girl. I wish I was still with her.'

Later, when I went to Moret with him, I saw a large canvas he had painted of her. She sat on the banks of the Loing wearing, if I remember rightly, a big hat and a blue dress. The background was the trees on the far bank of the river and their reflections in the still water. It was painted with the small touches he then used and it resembled a piece of beautifully worked tapestry. It was kicking about his hotel bedroom when I last saw it.

It was the loss of the Finn, or perhaps finding himself back in Paris with money in his pocket - I do not know - but now Rowley began to drink more than ever. For some days he did no work but he continued to share my room. He was always going to return to Moret the following day and it did not seem worth while finding a place to sleep. But day after day went by and he stayed on in Paris. At the end of two weeks my hotel proprietor came to me and explained that he could not be expected to put up two people for the price of one. We must either take a larger room or leave. 'And moreover he is so often drunk, your friend. Why, I have seen you carry him through the door and along the passage more than once.'

The ROWLEY SMART MEMOIR -4

The painter Sam Granowsky at the Rontonde with a couple of Parisian ladies.

La Rue Emile Zola, Malakoff, 1928, by Clifford Hall.

The artist Tsuguharu Foujita with his cat.

Kiki de Montparnasse.

A sketch of Kiki in the Dôme, 1928, by Clifford Hall.

.jpg)