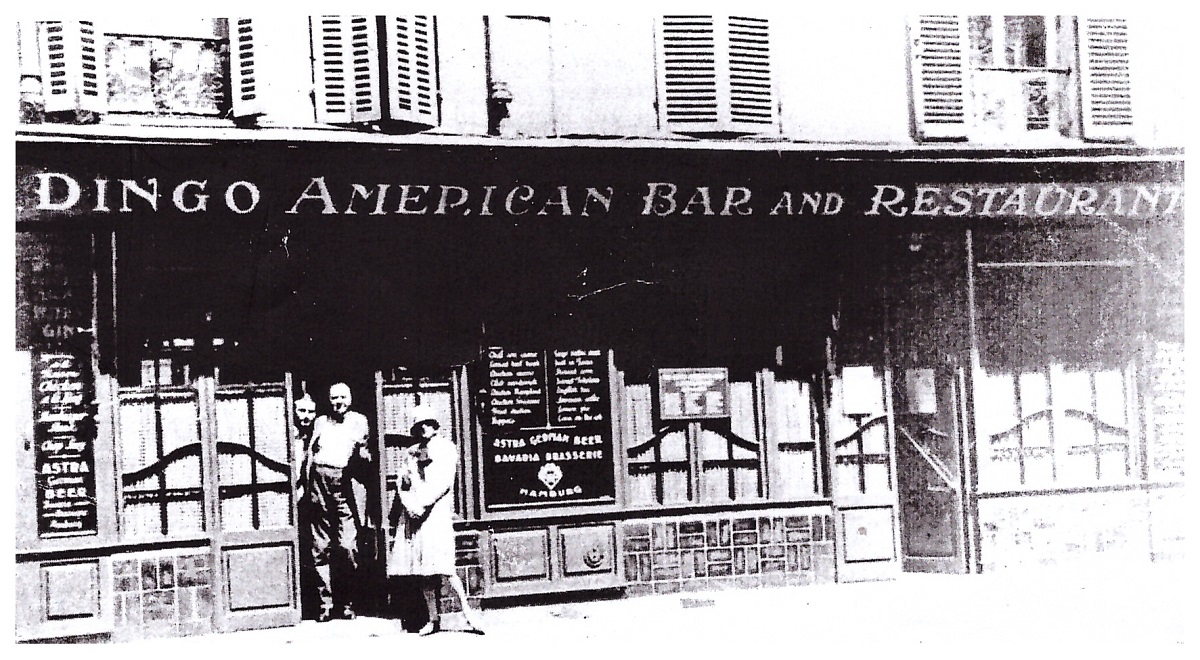

This I could not deny. I had given up trying to restrain Rowley. I had tried but he seemed desperate. He had lost interest in painting and seemed to think fatalistically that there was nothing to do, for the time being, but to drink himself into insensibility night after night. I had got rather tired of the business. For one thing I could not afford it, and it put me off working the following day. Rowley seemed to cling to me but he could not consider for a moment any other way of spending an evening than at the Dôme or the Dingo. 'Don't worry about me Cliff, I'll be all right.' But, a trifle hopefully, 'If you should be around latish just pick me up.' And I would go off to the Promenade of the Moulin Rouge or the Folies Bergères sometimes with Garralda and sometimes by myself with a sketch book in my pocket. Yet Rowley would be on my mind and I always made it my business to 'be around later'. First I would enquire at the Dingo in the rue Delambre, making myself heard with difficulty. There was always such a hell of a din in there, packed as it was with the noisiest drinkers of the Quarter, determined to have a good time. 'Mr Smart has been here, of course, but he left some time ago. A couple of guys were kinda helping him.' Rudolph the German barman had caught the American atmosphere of the bar. 'I guess they were going to the Dôme.' and so to the Dôme, pushing my way through the crowded interior and not finding him; going outside, searching among the sea of faces on the terrasse, finally asking a waiter who knew him or Monsieur Jambon the patron. 'Monsieur Smart? Yes. He was here. Comme toujours. He is gone to the Rotonde perhaps.' So I dodge through the traffic across to the Rotonde only to hear that Rowley has been practically carried out in the direction of the Select. And there I find him. Alone. Propped up in a chair on the terrasse; for some reason or other, the terrasse of the Select was seldom crowded. A small, rather pathetic little figure like a limp marionette - his collar turned up and his head sunk between his shoulders, his big nose poking out. His long hair all messed up, perhaps with sawdust in it, not vine leaves, where he had fallen on the floor of some bar. His big hat crammed down on his head, obviously put there anyhow, by a fellow reveller only a little less drunk than himself.

I speak to him. No reply. Shake him by the shoulder. No response. Pick him up, literally by the scruff of the neck and then, experimentally, leave go. He would fold up quietly into the chair once more as if his limbs were made of rubber, entirely without any rigidity. Sometimes he would mutter a greeting. He always seemed to know it was me, and then:- 'Can't walk. Goddam booze.' Or he might be so far gone that he was speechless. I must pick him up in my arms, for he weighed no more than a child, and carry him back to the hotel. It was only a couple of hundred yards away. Sometimes he might be able to stumble along by my side, holding on to me for support and muttering to himself. And at breakfast time he was bright eyed and good tempered. Perhaps he would refer to the night before: 'Guess I was drunk last night Cliff.' and that was all.

Quite often I found him in the second or third bar I visited. I got to know that his usual crawl was from the Dingo to the Select, a matter of three hundred and fifty yards at the most, and by way of the Dôme and the Rotonde. He did not always get as far as the Select. It all depended on who he had picked up at the other places and, I suppose, how they had been able to stay the pace.

Unlike many drinkers, Rowley was a great believer in food, particularly when there was what he called 'serious drinking' to be done. The Dingo gave you the finest pork chop, apple sauce, mashed potatoes and watercress in Paris. It was our favourite meal, round about 8 or 9 o'clock. In the early hours of the morning he would eat raw steak and lots of watercress, if he could get it. He was a great believer in watercress and said that it would always counteract the effects of drinking. If only it had! And he showed an almost childlike faith in fish as a means of combatting alcohol. 'Nothing like fish for breakfast, Cliff, fresh water fish if you can get it, and of course plenty of watercress. That's the thing to fix you up.' I used to imagine Rowley as a kind of battlefield on which fish and watercress waged unceasing war with the forces of alcohol. He took it all most seriously. In the mornings his one idea was to 'fix himself up'. In the evenings he just got himself in the state that would make the 'fixing up' vitally necessary again next day.

The time came to leave my hotel. For some days I had been anxiously waiting for money, owing me, to come from London. It did not arrive. After I had paid the hotel, with Rowley's help, I had only a few francs left. Rowley too had by now spent all his money. Our position did not worry him half as much as it worried me. He assured me that everything would be easy. We would just hang around for a few days, stay up all night in some café or try to borrow the fare to Moret. At Moret he could get credit for himself and for me too. I could pay him back when my money turned up. 'You will soon learn the first lesson, Cliff. It's dead easy to get all the drinks you want without paying for them, but it's damned hard trying to get anyone to buy you something to eat.'

Indeed I had already noticed this. More than once I had offered a drink to one or other of the girls who hung about the Dôme, only to be asked, a little sadly, if she could have a sandwich instead. And the drink would have cost more than the sandwich.

The technique of living practically without money was really very simple. The problem each day was to obtain one's 'entrance fee' as we called it, to a café. In other words to scrounge a drink or borrow the money for one. You were allowed to doze in your chair all night at the Select as long as you had a drink in front of you. It was even possible, if the worst came to the worst, to pass the night there on one drink. But Heaven help you if you forgot yourself and inadvertently emptied your glass, for if within a reasonable time you failed to order another, out you went! Food was the real problem, but there were ways of managing that too. The Dingo bar from about 5 onwards became our hunting ground.

As Rowley said, we both looked like artists and we would work the racket for all it was worth. If at times I had tried to look after him, he certainly made up for it now. He performed miracles. Somehow he managed, each day, to borrow the few francs that would make it possible for us to avoid being in the streets all night. And borrowing in Montparnasse was not easy. It was Rowley who, with unswerving discrimination, picked just the type of American who would be flattered to talk to a real artist in Montparnasse. The victim must be selected with care. He must already have had a few so that he would not notice anything strange when he was charged for whiskeys after, in reply to his offer of a drink, we had been served with beer. Rowley had 'fixed' this with the barman, Rudolph, who would slip us a sandwich apiece and pocket the difference between the price of a beer and sandwich and a whiskey. As far as I can remember a beer cost 3 francs 50 and a whiskey 12 or 15 francs. The sandwich wasn't much and when we had a good night Rudolph must have done pretty well, but at the time we thought the arrangement a very clever one. Sometimes those sandwiches were all we got to eat for days on end.

Before Rowley had managed this arrangement with Rudolph, Lou Wilson, the proprietor of the Dingo, had made him an offer. He would provide paint and canvas and one good meal a day plus beer if Rowley would paint a decoration to hang behind the bar. Rowley agreed and fixed it so that I would help him, thus get food and drink for us both. I suppose Wilson thought that if two of us were working on it the job would get done quicker. So, our food problem was settled for a while. We painted the decoration on a canvas with tempera colours. It was about 3 feet deep by about 8 feet long. We used a room to work in on the first floor above the Dingo Bar. It was also in this room that Wilson allowed us to store our luggage when we had had to leave the hotel.

I did not mind the conditions so much, the hell of this sort of life was not being able to paint. All one's energies were concentrated on getting something to eat, on obtaining, by some means, that precious but so necessary 'entrance fee' to some café that would at least give one the opportunity of getting an hour or two of sleep.

One morning I told Rowley that I must paint, I had done nothing for a week. 'All right Cliff, go ahead if you can get a canvas.' I got the canvas, on credit. From our favourite corner in more prosperous times, I started a sketch of the Boulevard with the kiosk on the corner and the long perspective of trees running away towards the Observatoire. I remember I gave that picture away, to someone I was very fond of; actually, I saw it only a short while ago and although I regretted that it was not better framed, yet seeing it again brought back to me the circumstances in which it was painted.

It is a sketch, no more, no better and no worse than thousands of others but when I looked at it again I remembered going to the colour merchant and asking for a canvas, telling him I had no money but would pay when I could. Triumphantly carrying off the canvas to Rowley and telling him I was going to paint again.

We sat on our favourite corner and I began to work. We ordered a couple of demis*, and we just hoped someone would happen along from whom we could borrow the money to pay the bill. I painted and as I painted Rowley continued to order more drinks. We began to have a formidable pile of saucers on our table. 'God knows how we can pay for it. We may stick here all night until some guy comes along and we can hang it on to him.'

* EG, a half of beer. Half a pint in Britain; usually 50cl in France. GRH

I remember that the pile of saucers on our table grew bigger and the waiter ostentatiously divided them into two piles as they threatened to overturn. They added up to twenty francs, maybe.

'Say, do you want to sell that picture?' We both turned quickly, nearly upsetting the toppling pile of saucers in our haste to connect with the questioner. The inevitable American, but he appeared genuine, bought drinks and sandwiches and paid for everything, saucers included, with a hundred franc note, one of an impressive looking roll that he carried in his pocket. It was Rowley who took charge of the situation, displaying a business sense that I would never have associated with him.

A price was at last agreed upon - 250 francs. I would have sold it for less but Rowley insisted on 250. 'Cliff will just sign it for you, you give him the 250 and take the picture right away.' What good fortune! Our fares to Moret, where we could live on credit, and some money over for paints and canvas. Everything seemed perfect but now there was a hitch. Our American had an appointment and he could not possibly carry a wet oil painting around with him. We suggested leaving it at his hotel, but he thought it would be best if I met him at the Dôme the following morning, with the picture. He would pay for it then. We both saw our good fortune slipping away, but neither of us liked to press the business too far in case the sale slipped away entirely.

The ROWLEY SMART MEMOIR -5

The Dingo Bar, Paris.

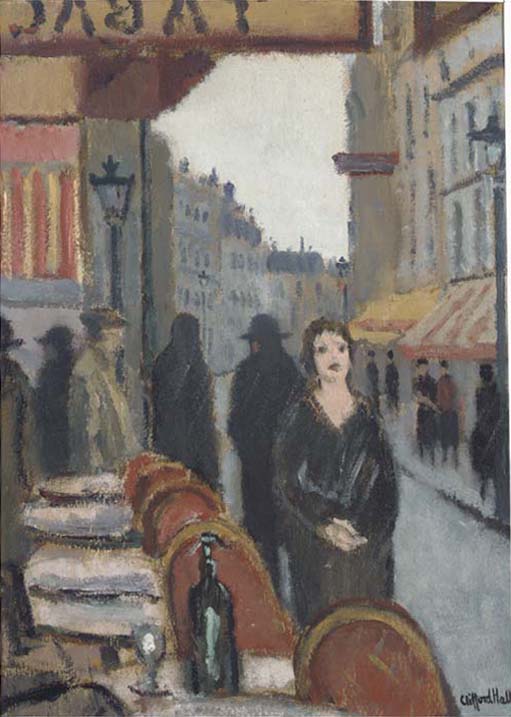

Couple in a Café by Clifford Hall. The signature indicates that this picture was probably created in London in 1927 or in Paris in early 1928.

Rue du Pot de Feu,Paris, by Rowley Smart. Now in the Atkinson Art Gallery Collection, Southport.

Rue des Abbesses, Paris, by Clifford Hall.

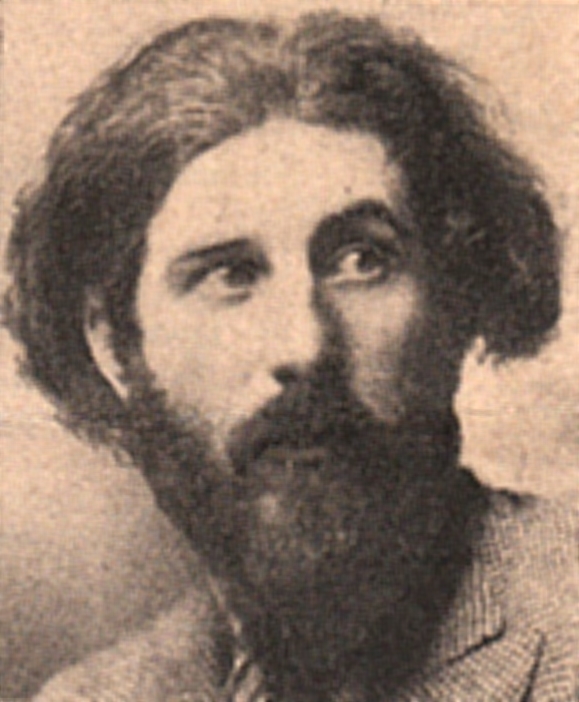

Rowley Smart (1837-1934). This photo was probably taken in Paris.