Finally, an appointment was made for 9.30 next morning. I was there on time with the picture and found the American having breakfast. He asked me to join him and I was glad to, for the previous night at the Dingo had been a bad one. Also I had walked to and from the English Theatre* near the Gare St Lazare after leaving him the day before, in wet leaking shoes, in an attempt to get a job painting scenery. So I placed the picture carefully against the wall and sat down to coffee and croissants. Rowley was anxiously hovering not far off and I thought it best not to hang two breakfasts on the American, particularly as he had paid up so well for yesterday's saucers. Anyway, Rowley and I would get a good meal as soon as the 250 francs was paid.

* This was probably the Théâtre de la Madeleine, which is built in the English style and is fairly near the Gare St Lazare train station. GRH

The American produced a cable. 'Look at that,' he said. 'I can't take your picture.' It said something about returning to New York immediately and there seemed nothing I could do about it. He said there was no time to pack the picture, it was still sticky and would need special packing, for he must leave that day. From the background Rowley had heard every word, he had crept closer when the cable had appeared and although I was horribly disappointed I could not help being amused at his dismayed expression. 'It was something quite unforeseen,' explained my client and he felt very bad about it. He knew it must be a disappointment for me. He reached for his hip pocket. Hope appeared again, for the hip pocket, I remembered, held the wad of notes. It was a moment of supreme excitement. Was he simply going to pay for the breakfast, or was he - ? I gazed at the roll of notes in his hand, fascinated. Very slowly he detached one for 100 francs and held it towards me. 'I realize that I have let you down. Will you take this for the trouble I have caused you?' he said. I hesitated, and I hesitated. I glanced up and saw Rowley, behind the American's back, making agonized gestures and mouthing 'Take it! For Christ's sake take it!'

'I can't take money for nothing,' I said. It seemed to me that the cable was an excuse. He had changed his mind about the picture and didn't really want it, and suddenly I became very foolish and proud and most determined. I would not take his money. He persuaded, he put the precious note on the table in front of me. I refused to touch it, and I really wanted it. It was most foolish of me. I wanted that note badly. How could I get it and still satisfy that silly pride of mine?

And then I remembered a portfolio of drawings that Lou Wilson had allowed me to leave in an unused room above the Dingo. I suggested that he choose a drawing for the 100 francs and he agreed that it could easily be packed flat at the bottom of his suitcase. Asking him to wait, I dashed out of the Dôme, round the corner and soon returned with my drawings. I am sure I appeared far too eager but he must have been a nice fellow after all, for he bought two drawings at 100 francs each.

We were saved.

I got Rowley off to Moret that very day. I was still hoping for a job at the English Theatre but it came to nothing in the end, and soon after I joined Rowley.

* * * * * * *

MORET

My first impression of Moret, and indeed the impression that remains with me still, was of a tiny compact little town hardly more than a village, but self-contained with no scattered houses on its edge. One left the country and abruptly entered the town. Moret les Sablons, the nearest railway station, was some distance away; you passed through the forest of Fontainebleau on the train. Moret itself stood near the fringe of the forest and on the banks of the fast-flowing Loing, a delightful river noted for its fishing and at that point about as wide as the Thames at, say, Goring. Approaching the town from the station one entered by an ancient stone archway built somewhat in the form of a tower. One was now in the Grande Rue, the main street, only a few hundred yards long, which ran downhill through another archway, similar to the first, on over the old stone bridge and so towards the canal, which just there paralleled the river, and into the country again. By the bridge there were flour mills, quite pleasing buildings in their way. Moret's chief attraction is the magnificent old church built on a rise in the ground towards the centre of the town. The church, seen from the far bank of the river with the bridge and archway in front, had been painted many times by Alfred Sisley, who may be said to have made the place famous as a resort for painters, much as Claude Monet made Giverny.

At Moret we both began to work regularly. One canvas in the mornings and another in the afternoon. Sometimes we went out painting together, sometimes I went off by myself. There was lots to paint and the weather was perfect. We both drank a great deal of wine but not too much - for a while. About six each evening we used to meet at a little café in the main street, the Select; for Moret too had its Select. Just one Pernod before dinner. We kept to just one. Leon Kelly, an American, a good friend of Rowley's, was usually there. I liked Leon immensely. He was a very talented painter. He helped me a great deal. He had married a French girl and they lived in a studio near the bridge, overlooking the river.

During the aperitif hour excitement was provided as we sat round the green painted table in the open front of the café that faced up the Grande Rue to the old stone archway which marked the finish to the town. About 6.30 every evening the waiter said, pointing up the road, 'Here come Monsieur Jack!' And at the top of the hill framed in the light coming through the archway we saw a dark figure on a bicycle getting larger and more distinct as it cruised down the hill at full speed, swaying alarmingly from side to side, missing disaster by millimetres. It was Jack en route to his evening Pernod at the Select. As he came abreast of us Jack gripped his brakes and steered towards the kerb. Some evenings he mounted fairly well, other times he fell off and the patron of the café rushed to help him up. It depended on the number of Pernods he had had on the way, but no matter how tight he was, Jack never fell off until he was opposite the Select. Sometimes we might be in time to catch him before he reached the ground. A stoutish middle-aged, not too clean shaven Englishman, he had been a vet in the army during the Great War. After the Armistice he had stayed in France and made a living doctoring cows and horses for the farmers round about Moret. Pernod was his passion. I have seen Jack's face every imaginable colour - mauve, yellow, red, green, blue. We used to have bets on it. Jack lived for Pernod; he would take five or six in a couple of hours , and that is hard going.

Dinner at the Auberge de la Terrasse, where Rowley and I stayed, was served out of doors in a kind of gravelled yard that opened out of the inn. It was enclosed on two sides by walls against which were a few creepers. At the far end was a stone parapet over which one could lean and look down on the bank of the Loing. Gaily coloured wash-house boats and a bath house were moored to the near bank. Beyond, on the other side, were tall trees, whilst above them and slightly to the left rose a hill. On fine summer evenings it became very lovely and one forgot the row of lavatories badly screened by a hedge of dusty privet that occupied one side of the yard. About half a dozen tables covered with gaily checked tablecloths were placed haphazardly. Behind the lavatories a flight of stone steps led down to the river bank. On fine Sundays the high old-fashioned pay desk of dark wood was moved, with a great deal of trouble, from its usual place in the hall out into the yard - I should really call it the terrasse.

Then the local fishmonger, sixtyish, with short white hair, resplendent in a frock coat, a thin streak of coloured ribbon in the buttonhole, presided at 'la caisse', solemnly shook you by the hand and wrote mysterious things in a huge ledger, tracing lines and figures with a slow, spidery precision, holding the pen in his great red paw that had thick golden hairs on its back. A delightful fellow, this fishmonger. He shook hands with everyone, he beamed good-naturedly. In the mornings Rowley and I used to see him at his fish stall, in the town near the church, his shirt sleeves rolled up over muscular arms which were now covered with fish scales. He roared a greeting and then gravely, with a kind of sideways twist, presented you with his elbow or upper arm to be shaken. I believe when he was alone he shook hands with himself. Rowley got on very well with him; neither understood a word the other said but Rowley had, through me, told the fishmonger what an indispensable article fish was for 'fixing you up in the morning'.

We did not sleep late in the mornings although we were seldom in bed before 1am. About 9, Rowley dragged me off to buy fish, which we took round the corner to Leon's studio. Leon, pottering about in pyjamas, fussed with a canvas, and his wife sat up in bed yawning like some sleepy animal. 'Come on Leon, tell her to fix that fish, nothing like it for breakfast. We have got some watercress, too.' And Marcelle got up slowly from among the tumbled bedclothes, still heavy-eyed and yawning, and throwing an old shawl over her nightdress began to cook the fish. I slipped downstairs for a jug of coffee from the nearest café and by the time I got back the fish was nearly ready. I never touched it myself, could not be bothered with the bones, but I usually nibbled some watercress to please Rowley. Moret was famous for its watercress, there were large beds of it growing near the river. Rowley was delighted when he discovered he was sure of a constant supply of this wonderful food - a sure remedy for hangover. It seemed to work with him, that and the fish, at least for a time. Perhaps because he believed in them.

On my way up the uncarpeted stairs with the jug of coffee I might pass Moret's only whore wrapped in a soiled dressing gown on her way to the café for a morning coffee and a petit verre. She moved slowly on her wooden leg, her hair tousled and her face still with the traces of the previous night's make-up. After dark she haunted the streets, standing in her doorway listening for the footfalls of possible clients. For after dark the little town was very still. The cafés closed at 11 p.m. There were no lights showing in the houses for most people went to bed early. I do not remember street lamps. Always the last to leave, we came out of the Select into the dark night.

The ROWLEY SMART MEMOIR -6

Theatre Scene, Paris, by Clifford Hall. Painted in Paris circa 1928, this painting is a good early example of the artist's unusual point-of-view and his recurring interest in painting subjects reflected in mirrors. However, it also clearly displays the influence of his teacher, Walter Sickert.

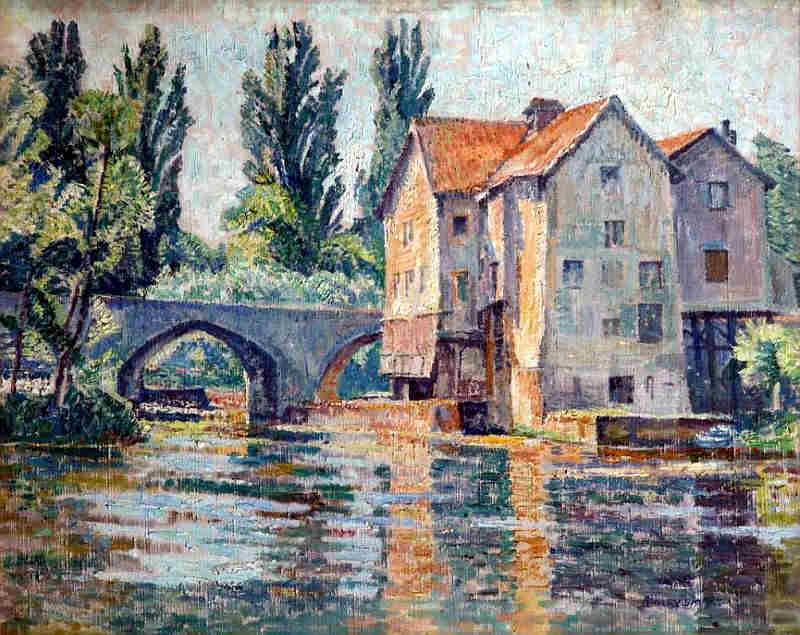

The Mill, Moret-sur-Loing, France, by Rowley Smart.

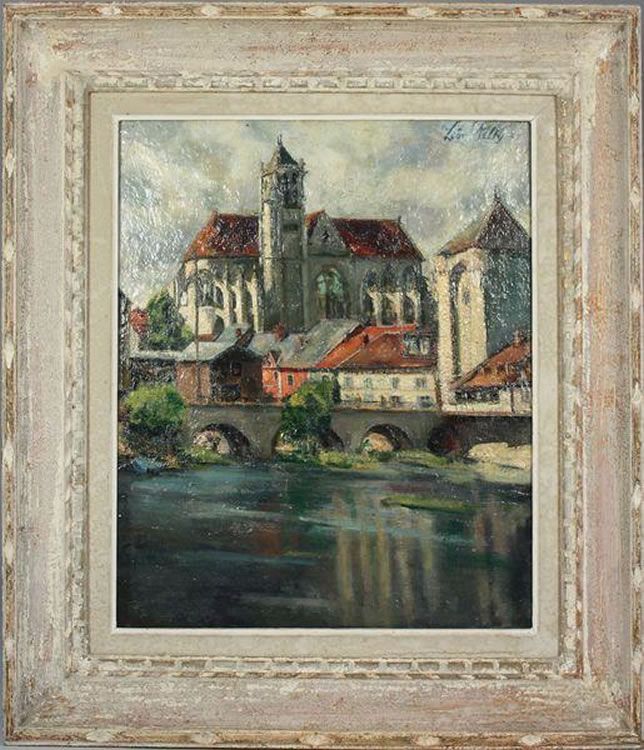

Vu de Moret-sur-Loing by Leon Kelly (1901-1982).

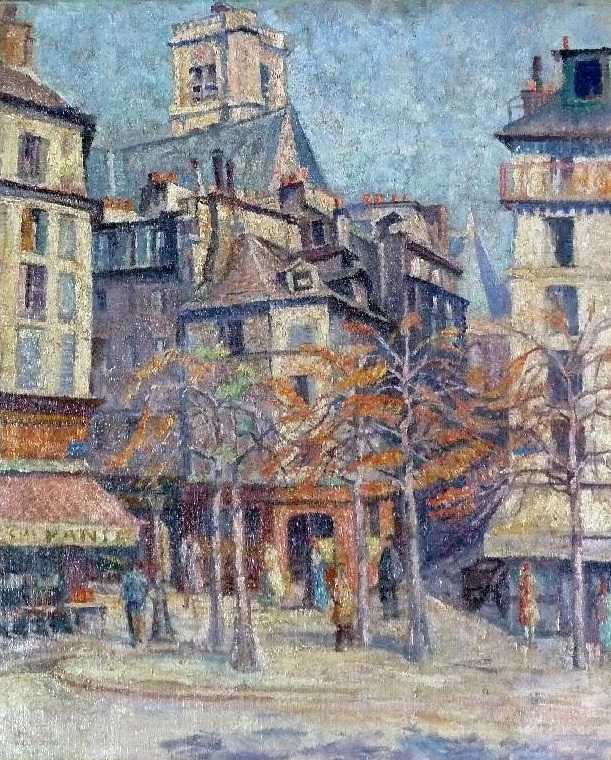

Old Paris by Rowley Smart.