No traffic and the streets practically deserted. Away down by the bridge the beam of an electric torch wandered, momentarily lighting up a close-shuttered window, throwing into sharp light and shade the cornice of a building or the edge of a kerb and the pavé. Moret's only whore was searching for someone to take home, up those creaking wooden stairs and through the long dark passage, to her room beneath Leon's studio. She has heard our voices and the beam of light swings in our direction to be focussed on our faces. She stays in the doorway and as we come close greets us. I suppose she did not want us to notice her uneven walk and awkward movements caused by that wretched artificial leg. But soon she gave up accosting us. Leon once assured me that she did fairly well, holding as she did in Moret the monopoly of her profession.

Somehow wherever I found myself with Rowley I found drunks. As I read through what I have written so far, the main theme seems to be alcohol. I find it on almost every page and I suspect you have already begun to wonder if we knew any really sober people.

It is fascinating to discover or to imagine one has discovered reasons for conduct. In oneself and in others. It is too easy to dismiss a drunk as merely weak-willed. Many weak-willed people do not drink or use other drugs. I think Rowley drank because he wanted companionship, for when he had stopped working he felt bored. Possibly his boredom had, at the beginning, grown out of unhappiness. I do not know. He could not, after a day's painting, sustain an intellectual conversation for long, although he liked to be with intelligent people; but as I watched the antics of some of his drinking companions, I felt that our painter must have his clowns to amuse him. And he was the greatest clown of them all when he was in the mood. He used to say it was a good thing that I kept my legs, otherwise he might never get home. He had something in him that simply asked to be looked after.

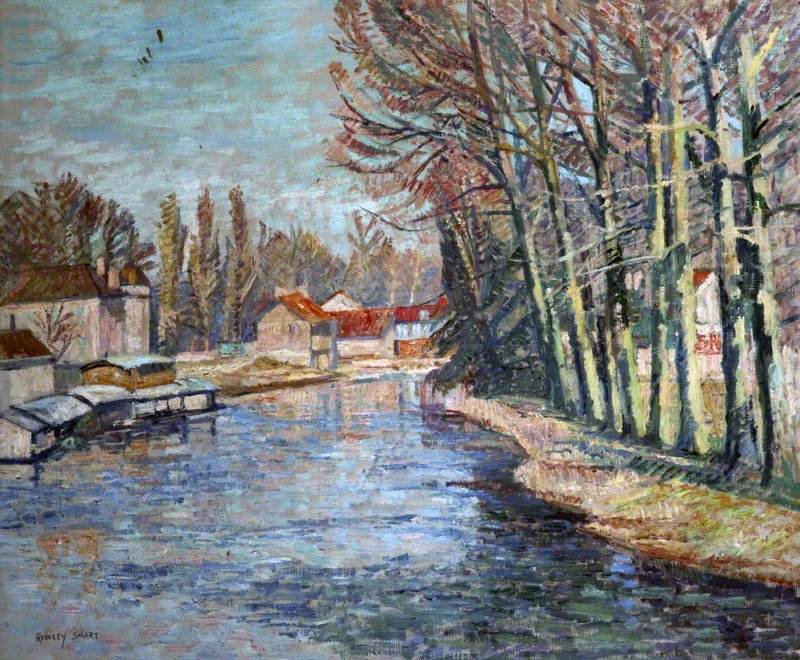

Unlike most of his companions, Rowley worked. That alone endeared him to me. And then he worked so well. His oils at that time were glittering things, full of colour and light. I feel that they were not very profound, but they expressed such delight in the coloured appearance of things in sunlight. He became profound later on, when perhaps he realized at last that there were only a few years left.

And so leaving Leon at the door of his studio we go on down the sleeping street towards the great chestnut trees that stand before the inn. Rowley was going to paint those trees. I wonder if he ever did. And Pierre the landlord is waiting up for us. Pierre, drunk and a trifle annoyed that we have been spending our money at the Select and not with him.

Pierre - short and thickset like a little bull. His thick black hair commencing such a short way from his heavy eyebrows under which little eyes look straight out, piercingly.

'A brandy, Pierre, before we go to bed,' I say, and Pierre, softened, leads the way into the darkened bar, turns up the lights and setting three glasses and a bottle on the counter, pours out a generous measure. And after another, 'C'est avec moi, Messieurs.' Pierre looks at me and says with his deep gruff voice, 'Ah you think too much Monsieur Clifford. It is a great mistake. I too, I think too much. During the war I was with the ambulance. With this hand I have killed Frenchmen, my own countrymen. Shot them. They begged me to do it, to end their agony. And I did. There was nothing else to do, but I cannot forget.' And Pierre must pour out another brandy, slopping it over the counter with a shaking hand.

I persuade Rowley to come up to bed, telling him it will be fine tomorrow and he wants to finish his picture. We leave Pierre, sitting now, his elbows on the table, dark and glowering, the eternal black stubble framing his face, a brutal face in which strangely kind piercing eyes stare out at the opposite wall, past the half-empty brandy bottle and the coarse, squat little glasses.

We creep up the stairs to Rowley's room on the first floor. 'Come in a moment and just have a last cigarette. I'm not drunk, only I can't sleep, and I don't want you to go just yet. Stay and talk a while.' He falls on the bed still in his clothes and I pull a blanket over him. We talk for a while. He lies on his back and I can see the red glowing tip of his cigarette, and if I turn my head I dimly sense the trees on the far bank of the river and in the stillness I hear the wind gently moving their leaves. There is a slight movement behind me and the red cigarette tip begins to move slowly downward and then stops. He has taken it from his lips. The cigarette still glows between the long fingers of his hand lying limply just over the edge of the bed. His voice dies away. I carefully take the cigarette from him. I wait a few more minutes to make sure he is really asleep. At last I leave him, closing the door carefully, and I go up the next flight of stairs to my own room that also looks over the river towards the dark rustling trees on the far bank.

For a few weeks Rowley had behaved himself reasonably well, then the weather broke and it rained for some days. Work was interrupted. But apart from the weather, Rowley had struck a dull patch. Every artist does from time to time. He had been working hard and now he talked of leaving Moret and going back to Paris. The country was beginning to bore him and he wanted to see Montparnasse again. Meanwhile there was another money hitch so he had to remain in Moret, whether he liked it or not, cursing the bastards who bought his work and then kept him waiting for the money and the rain which would not let him finish his pictures.

The Auberge was full. Several American painters with their wives, Willy Gilman and little Lucette from the Dôme, and a Pernod fiend whom Rowley nicknamed the Duchess of Canada, and Danilevsky with his ukulele. Danny soon learned all Rowley's favourite songs. He played well and he played incessantly. Rowley was delighted. With such a willing accompanist always there when he was wanted there was no excuse for not joining in the choruses of 'Barnacle Bill' and 'The Sentimental Skipper'. Rowley's father** turned up from Manchester. He was a quiet old chap and sometimes he ventured to suggest that Rowley took things a little more quietly. This only made Rowley very angry. 'The old man is all right but why the hell can't he leave me alone? He gets on my nerves.' The father was a sedate, older edition of the son, with less personality, but about the same height and with the same big nose. He used to come sketching with us, carrying Rowley's paint box. He stretched his canvas and attempted to wash his brushes. When it was hot Rowley generally sent him off to the nearest café for cannettes of beer. He was lonely, I am sure, and I talked to him often but I never heard him say what he thought of his son's work. He talked a lot but I cannot remember a word he said. He went to bed early and if he did come with us to the Select he never stayed for more than a couple of drinks. I believe Rowley had to keep him. Years after, Rowley said that the old man had spoiled a lot of his paintings by oiling and then varnishing, making them go horrid and yellow. Rowley was furious.

* This was possibly William Gilman Low (1844 – 1936) an American artist who painted some landscapes in France.

** Thomas Smart, a grocer, born circa 1863 in Altrincham, Cheshire (now in the Greater Manchaster area). GRH

Pierre was doing well. Every room in the place was taken and he decided to have a raised wooden platform built jutting over the river, on which diners would have their food and admire the view. There was a deal of planning and consultations with the builder and one morning a couple of workmen carried a lot of great wooden piles into the yard and started to dig holes to receive them. Now this leads up to the 'Duchess of Canada' for she fell into one of the holes and Rowley and I hooked her out, and that is how we got to know her. She was not a very attractive person, and although she had let us see that she was dying to join our party we had not encouraged her. Danilevsky treated her abominably. He took a sadistic pleasure in encouraging her to drink until she became quite crazy. And Danny saw to it that she bought him plenty of wine. It never had any effect on him, that I could see.

When the weather was bad we ate indoors in a large room that ran from back to front of the inn. Danny sat at the Duchess' table. Tilting back in his chair apparently not very interested in the food, his eyes half closed, he made me think of a sleepy cat; only this cat smoked Russian cigarettes, drank red wine or Pernod and played with a ukulele. The claws were there though; and as the evening wore on Danny's music became more urgent, with something hard and compelling about it.

He plied his companion with drink, she was paying, and his own glass was never empty. 'Come on you old bitch, I'm bored! Give us a dance,' Danny roused her. 'And take another shot of Pernod to liven you up!' He began to play again and the Duchess jumped from her chair, finished her drink and danced. Danny sat there, tilting backwards, smoke rising from the cigarette in the corner of his mouth. His attitude was indolent but the dark brown eyes, still half closed, now looked cruel and gleamed viciously. 'Faster, put some guts into it!' The poor Duchess gasped and whirled as the rhythm of the music quickened. She whipped off her dress and danced naked. I was surprised the first time it happened and I realized her frock was her only garment. Her thin body leaped in complete abandon whilst Danny smiled softly, showing white teeth. Never changing his lolling pose he played with frenzy until the dancer, utterly exhausted, fell to the floor. Danny had achieved the climax I knew he had been planning for hours. He got up and glancing at his victim drawled 'Bloody old fool. Guess I'll take a look outside.'

The rain has stopped and after a little while I hear the sound of Danny's playing again. I walk out to the terrasse. The air is fresh, lovely after the rain. The wet gravel crunches under my feet, behind me Rowley shouts to Pierre for another drink. At the far end of the terrasse I can see Danny, his white shirt and pale face showing clearly in the moonlight. He is sitting on a corner of the stone parapet, leaning lazily against the wall, overlooking the river. He is a white silhouette against the dark trees. His head thrown back, he stares at the moon sailing high above us. But now he plays a sad Russian song and he plays with such exquisite feeling that I stand quiet and listen, wondering. Indoors, Pierre's wife and her sister are helping the Duchess up the stairs to bed.

The ROWLEY SMART MEMOIR -7

This photograph shows the building in Cheetham (Hill), Manchester, where Rowley Smart is believed to have been born in 1887. It was on the corner of Johnson Street and Smedley Lane. Rowley's father, Thomas Smart, probably worked in the grocer's shop. In the 1891 census, the family were listed as living at 18 Smedley Lane and in the 1911 census at 4 Johnson Lane. There has been a lot of redevelopment in the area and Johnson Street, Cheetham Hill, no longer exists.

Rue du Pavé Neuf, Moret sur Loing by Clifford Hall. Photo credit: Whyte's Auctions, Dublin.

Moret-sur-Loing by Rowley Smart. Now in the collection of the Towneley Hall Art Gallery & Museum.

River Scene by Rowley Smart. Now in the collection of the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

Mill at Giverny by Rowley Smart.